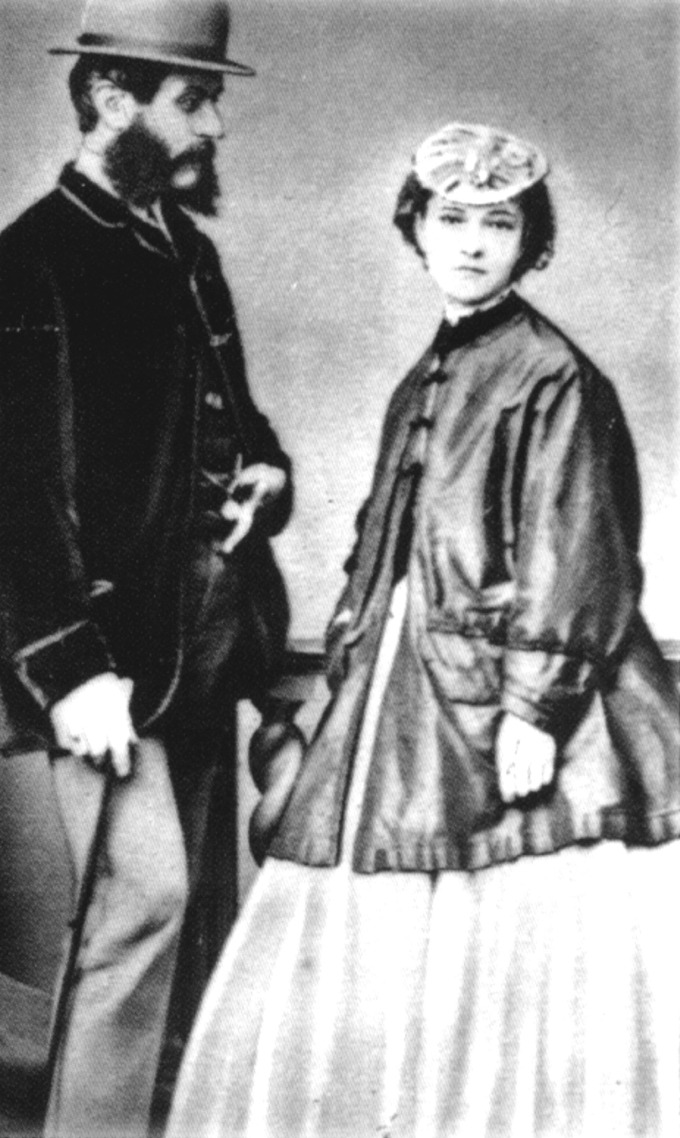

Eugene Chantrelle and his 16-year-old pregnant wife Elizabeth on their wedding day

Eugene Chantrelle and his 16-year-old pregnant wife Elizabeth on their wedding day

ROBERT Louis Stevenson was in his mid-twenties when he first met a psychopath. By all appearances Eugene Marie Chantrelle seemed a normal, civilized, well-educated human being – not a brutal sex criminal capable of killing without the slightest moral qualm.

Only when the Frenchman was suddenly arrested for the murder of his wife did the young Scottish author realise the shocking truth he would one day reveal in Jekyll & Hyde – that ‘Man is not truly one, but truly two’.

Chantrelle was a failed doctor, having been forced to give up his medical studies in the French city of Nantes when his ship-owning father went bankrupt – yet his Hyde side was only too successful in a long career of clandestine depravity.

When Stevenson knew him he was a respectable family man, giving French lessons in local schools and privately.

They would meet occasionally at the Edinburgh home of Stevenson’s old French master Victor Richon, along with Henri Van Laun, a successful author of French textbooks and translations – much to the envy of Chantrelle.

‘One evening he met me on the street, and asked me if I had seen Van Laun’s translation of Molière,’ recalled Stevenson, who spent much of his time in Bohemian artist colonies in France and liked to keep up his conversational French.

‘When I told him I had, and confessed that I could see no merit in that piece of work, his eyes blazed with hope, he had me to a public house; and bidding me name any passage in Molière with which I was well acquainted, offered to improvise without book a better version than Van Laun’s.

‘I accepted the challenge; and he, as far as I was in a position to judge, did well what he professed…’

Chantrelle’s professional jealousy was only human, when he was struggling to make enough to support his wife and the two sons on whom, by all accounts, he doted.

But his response to the problem was psychopathic – he would take out a large insurance policy on his wife’s life and then, quite calmly, poison her.

Elizabeth Dyer had soon regretted her first meeting with Chantrelle when he taught her as a 15-year-old pupil at Newington Academy. Nine months in an English jail for an indecent assault on a girl pupil had not curbed his gross sexual appetites and soon poor Lizzie found she was pregnant.

Chantrelle had got a girl ‘into trouble’ before, on New Year’s Day, 1867, when a young woman called Lucy Holme called at his home in Edinburgh’s George Street in response to his advertisement for a housekeeper.

She found him alone and, during their interview, he offered her a glass of claret. When she declined the drink and whatever he had put in it, Chantrelle callously raped her.

Too ashamed to go to the police, Miss Holme found a situation as a governess in England until it became clear she was pregnant. Desperately she wrote to Chantrelle, begging him to help her: ‘You, and you only, are the father of the child, and if I should not get over it, you too will be responsible for my death…’

Seemingly devoid of feeling, Chantrelle did not even bother to reply, leaving her to bring up the child alone. But when Lizzie Dyer was in the same predicament, her family threatened him with ruin if he did not marry her.

It was an unhappy marriage in which he ‘beat her, kicked her, caned her, cursed her’ as well as fathering a second son and, shortly before the murder, another baby. When angry, he often threatened to poison her.

Lizzie fled several times to her family but would not seek a divorce because she did not want to bring shame on the children.

Meanwhile Chantrelle, after drinking his daily bottle of whisky, would leave the house in a rage with a loaded gun in his pocket to vent his lust in the brothels of Clyde Street. There, if displeased, he would shoot out the windows, to the terror of the girls and their other customers.

Trapped at home, his wife feared for her life yet seemed powerless to act, telling her mother: ‘Mama, my life is insured now and you will see that my life will go soon.’

The failed doctor chose New Year’s Day, 1878, for his attempt at the perfect crime. Eleven years to the day since raping Lucy Holme in the same house, he administered a fatal dose of opium to his wife, hidden in an orange or possibly a glass of lemonade.

Next morning, the maid found her moaning and unconscious. When a real doctor was called, Chantrelle claimed his wife had been poisoned by a gas leak – he could only claim the £1,000 if her death was an accident.

When she died later that day, he maintained the same story to the police, yet her body showed no signs of coal gas poisoning. The symptoms suggested an overdose of narcotics, but no traces of opium were found.

Lizzie’s body was released for burial – in her wedding dress, by bizarre request of her ‘grief-stricken’ husband, who had to be restrained from hurling himself melodramatically into the open grave.

But further investigation uncovered the nightdress she had worn before her death, with vomit stains containing enough opium to kill. Chemist’s records showed Chantrelle had purchased a large quantity of the drug which had since disappeared. It was enough to persuade a jury he should hang.

For Stevenson, present in court throughout the trial of his former acquaintance, it was a traumatic experience. As the evidence unfolded he found himself, like Dr Jekyll, ‘aghast before the acts of Edward Hyde’.

He was there when Barbara Kay, mistress of a Clyde Street brothel, was called as a witness – and experienced the wave of relief when she was stood down without giving evidence that might have incriminated other respectable family men in the courtroom.

Finally Stevenson heard Chantrelle’s rambling protestations of innocence after the judge donned his black cap and pronounced the death sentence ‘for doom’.

But more shocking still was the information which Stevenson, a qualified advocate, was given by the prosecution team – that Chantrelle was believed to have committed other murders in France and England and that since his arrival in Edinburgh, ‘more than four or five had fallen a victim to his little supper parties and his favourite dish of toasted cheese and opium’.

For all this, Chantrelle paid the penalty when Marwood the hangman dispatched him with an eight-foot drop and a black flag was raised over the Calton Jail to let the crowds outside know the murderer was dead.

Stevenson was not then in Edinburgh but the things he had learned during the trial of Eugene Marie Chantrelle would remain with him for life. Most shocking of all was the way in which such a monster had been able to deceive everyone.

On reflection, Stevenson wrote: ‘I should say, looking back from the unfair superior ground of subsequent knowledge, that Chantrelle bore upon his brow the most open marks of criminality… if I had not met another man who was his exact counterpart in looks, and who was yet, by all that I could learn of him, a model of kindness and good conduct.’

Meanwhile one other piece of evidence from the trial stuck in the author’s mind. At the time of the murder, Chantrelle had run up a large butcher’s bill which he could not afford to pay. The name of the butcher was Jockel & Son.